Middelburg – A fierce intermittent stench signals a time-ticking bomb as untreated sewage flows directly into a stream feeding the Klein Olifants River in the Steve Tshwete municipality.

“We cannot tolerate the smell, especially in hot weather; it becomes impossible trying to eat around that time when the smell is so strong, unless you want to throw up,” said one resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity as they are an employee of the municipality and not authorised to speak to the media.

The Olifants River is a lifeline for millions, providing drinking water, agricultural support, and fishing opportunities in the Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces.The effluent is gushing from a manhole connected to a pipeline that transports wastewater to a treatment facility.

The stream, originating from groundwater, merges with the Klein Olifants River, which is fed by the Middelburg Dam and serves as a water source for the local municipality.

The contamination not only threatens local fish and crabs but also endangers residents by increasing the risk of waterborne diseases.

This unsettling situation paints a vivid picture of neglect, highlighting the critical shortcomings in municipal waste management systems.

The consequences of such negligence are dire, posing significant risks to both public health and local ecosystems.

Disrupting sites of spiritual practices

This environmental neglect is more than an ecological issue ; it disrupts long-standing spiritual practices integral to the cultural identity of local communities. These practices, deeply woven into the fabric of societal life, have historically relied on the river as a site of reverence and connection to ancestral traditions.

One resident, identified himself as Ras Symbol K, said he relies on the stream for religious ceremonies.

“This is where I typically perform my rituals. Every month I come here for cleansing. This water is crucial for both my physical and spiritual purification,” he said. “But now that the water has been altered, I no longer use it because it is dirty. That disturbs my spirit.”

The wastewater appears to have adversely affected the local fish and crabs that once inhabited the area. “I no longer see them around. I believe it’s related to the pollution occurring here,” said Ras Symbol K.

Ras Symbol K’s sentiments were shared by fellow resident Mandla Siwela, who highlighted how crucial groundwater is for his faith. “It’s quite concerning,” he said . “We rely heavily on this water. We fill up two-liter bottles and bring them to church to be blessed. Some people use it for bathing, while others drink it or sprinkle it around their homes, depending on their needs or challenges.”

Sipho Sibanyoni raised concerns regarding the potential health implications. He stated, “We have children who play in the area. My fear is that they may come into contact with the wastewater, putting them at risk of becoming ill from germs and bacteria.”

Waiting for statistical report from the Rockdale Community Health Centre/ Clinic on illnesses such as cholera, diarrhea, typhoid etc spread through contaminated water

Section 28 of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) specifies the obligations of individuals or entities responsible for causing or potentially causing pollution. They are required to take appropriate actions to prevent, stop, or reduce the effects of their pollution. Along this is the National Water Act (NWA), which emphasises the importance of preventing pollution and providing guidelines for managing threats to water resources.

The Act also makes provision for the “polluter pays principle”, which holds polluters accountable for environmental damages, ensuring that those responsible bear the costs of their actions rather than passing those burdens onto the local communities.

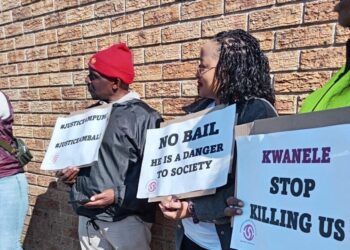

‘We expect municipalities to uphold their responsibilities’

The Steve Tshwete Local Municipality is, by application of the NEMA and NWA, guilty of polluting the Olifants River. We asked the municipality about this incident. It acknowledged the situation and said they are addressing it.

“The team attempted to open this blockage using the rods, and not yet successful, we are in progress of acquiring external assistance as our jetting truck is in for repairs,” said Steve Tshwete municipal spokesperson Lerato Kgomo.

They also pointed a finger at the residents, suggesting that unauthorised dumping could be the culprit behind the blockages. “The biggest challenge is the amount of foreign items thrown into the sewer lines, things like old shoes and bottles.”

During the Rivers Clean-Up campaign in Emalahleni last week, Mpumalanga’s MEC for Cooperative Governance, Human Settlements and Traditional Affairs, Speed Mashilo, unveiled plans to impose penalties on municipalities that persist in contaminating water resources.

Reports indicate that several municipalities in the province have been found culpable of polluting rivers and dams with untreated sewage, admitting their violations of NEMA regulations.

Mashilo emphasised that these forthcoming fines will be allocated to support municipalities and mitigate the effects of pollution. “We expect municipalities to uphold their responsibilities. Therefore, we will be implementing penalties—fees that need to be paid so we can hire individuals to purify these rivers. Those who pollute must fully own up to their actions,” he said.

‘Implement the polluter pays principle’

Matthews Hlabane, the chairperson of the South African Green Revolutionary Council (SAGRC), told Highveld Chronicle about the pressing concerns surrounding environmental health within the Steve Tshwete municipality.

Hlabane’s organisation is pushing the Department of Water Affairs to promptly implement the polluter pays principle in the municipality.

“Upon observing the alarming conditions in Steve Tshwete, we cannot turn a blind eye to the consequences that are unfolding,” Hlabane said. “The improperly managed sewage flows are not just an eyesore; they are a direct threat to the well-being of surrounding communities. We have concrete evidence to suggest that this pollution is linked to various health issues, which ultimately puts community members at grave risk, leaving them as unwitting victims of negligence whose costs are unjustly externalised.”

Hlabane pointed out, with a tone that conveyed both urgency and understanding of the sensitivity of the situation. “These are not mere administrative issues; they touch upon the very core of public health. The well-being of not just the residents of Steve Tshwete, but also many communities downstream, hangs in the balance. We are calling for a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to address environmental health and ensure that no community is left vulnerable.”

The time for change, he insists, is now.